There is no glory in pulling residual penetrating filler stain out of planking. However the returns for doing so are worth the drudgery and elbow grease involved. Sandpaper does not fill up as quickly, and subsequent bleaching delivers a materially more uniform result.

Our tools for the job: sandvik scraper with forward hand hold, heavy duty stainless steel scrubber, stiff-bristled brass brush, and Circa 1850 Heavy Duty Paint and Varnish Remover. I have experimented with several scrubbers, but the one that we find most effective is available from Amazon.com. Search for “Heavy Duty Stainless Steel Scrubbers, 3.5” large Diameter…” A pack of twelve is $12.99 on Amazon Prime.

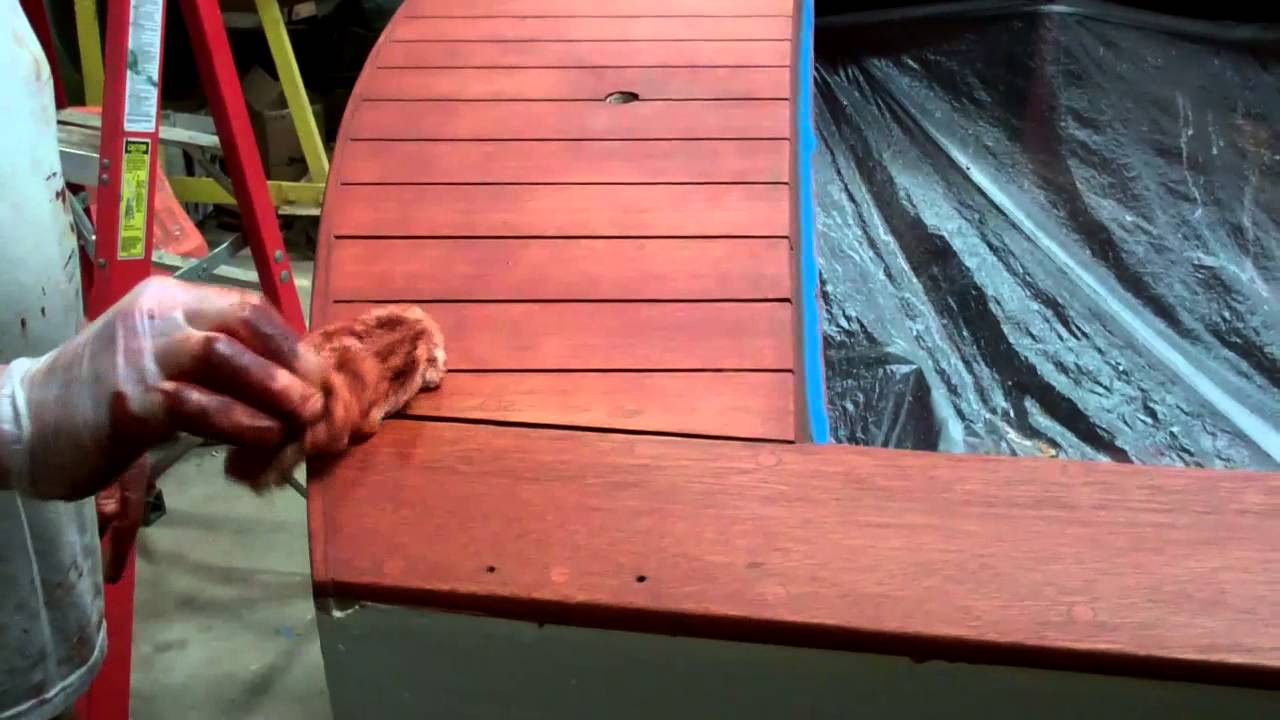

I had previously made four passes, mostly with the scraper and brush, and one with the scrubber on the transom in the clip. Now I continue with one additional scraper and brush passes and two scrubber passes.

My hope is that the camera picked up the increasing difference between the area worked and that surrounding it. An additional plus is that, after seven or eight passes, we become intimately familiar with the planking, its fasteners and bungs, which also renders discovering blemishes or damage needing Dutchman repairs quite straightforward.

Once the cleaning is complete, we will flat board the topsides and transom with 80 grit, making sure we do not leave any cross-grain scratches, before we proceed to bleaching, staining, sealing and varnishing.